Home

> Musings: Main

> Archive (this is first Archive page)

| Introduction

| e-mail announcements

| Contact

Musings: 2025 (archive)

Musings is an informal newsletter mainly highlighting recent science. It is intended as both fun and instructive. See the Introduction, listed below and in the navigation bar at the top, for more information.

In mid-2023, Musings transitioned to a new format, for a semi-retirement phase. With some adjustments, it is now similar to the earlier "briefly noted" format. The format is flexible, and contributions can be in various formats by agreement.

If you got here from a search engine... Do a simple text search of this page to find your topic. Searches for a single word (or root) are most likely to work.

Introduction (separate page).

This page:

2025

December

November

October

September

August

July

June

May

April

March

February

January

Also see the complete listing of Musings pages, immediately below.

All pages:

Most recent posts

2026.

2025: this page, see detail above

2024

2023:

January-April

May-December

2022:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2021:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2020:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2019:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2018:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2017:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2016:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2015:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2014:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2013:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2012:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2011:

January-April

May-August

September-December

2010:

January-June

July-December

2009

2008

Links to external sites will open in a new tab.

Archive items may be edited, to condense them a bit or to update links. Some links may require a subscription for full access, but I try to provide at least one useful open source for most items.

Please let me know of any broken links you find -- on my Musings pages or any of my web pages. Personal reports are often the first way I find out about such a problem.

New items

December 2025

What if your clothes could listen to what you say?

December 10, 2025

That headline may sound odd. More important is the technology developed in the new work.

The underlying development is a simple way to convert sound to an electrical signal. That almost sounds like a microphone. But this "microphone" is a piece of "cloth" that can be embedded in your clothing.

Sound, including speech, involves air pressure waves. Those waves can be sensed by the membranes in your ears -- or by pressure-sensitive materials in your clothes. The trick was to develop materials that could do this usefully in the clothing context. The scientists ended up using silicone rubber embedded with tiny nanoflowers of tin sulfide. Sound waves, from speech, cause movement in the material. Friction, which leads to electricity. The general idea there is called triboelectotricity.

Importantly, the material is fully compatible with ordinary clothing, including ordinary washing. And it lets your clothes communicate with ChatGPT, or such. We'll skip the applications here. As the technology becomes practical, we can sort out applications later.

* News stories:

- Chinese researchers develop innovative textile that helps AI recognize voice commands. (China Daily, October 13, 2025.)

- Smart Clothes That Hear: A-Textile AI-Powered Voice Control Woven In. (Neha Adikane, ENTECH Digital Magazine

(STEM Magazine for Teens), October 16, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Deep learning-empowered triboelectric acoustic textile for voice perception and intuitive generative AI-voice access on clothing. (Beibei Shao et al, Science Advances 11:eadx3348, October 8, 2025.)

Another triboelectric generator: Using ultrasound to recharge an implanted medical device (October 19, 2019).

More nanoflowers: Better enzymes through nanoflowers (July 7, 2012).

mRNA vaccine for flu: a Phase 3 trial in humans

December 3, 2025

The key overall result from a Phase 3 clinical trial in humans, involving protection against influenza in "the real world"... The mRNA vaccine was somewhat more effective against flu than the conventional vaccine. To facilitate direct comparison of old and new vaccines, the two vaccines targeted the same virus strains. The mRNA vaccine also led to more side effects; nothing serious, but not good for the vaccine's public merge.

The big reason for the interest is the time needed to make the vaccine. The flu vaccine is reformulated each year, to target then-current strains. With the conventional vaccine, making the new vaccine is a slow process, and the virus population of concern often changes after the vaccine has been set. It is a general advantage of the process for making mRNA vaccines that the lead time is much less. This should give the mRNA vaccine an advantage; it should turn out to more closely match the virus strains that are actually circulating during vaccine use.

* News story: Experimental mRNA flu vaccine is more effective than conventional flu shot, but causes more side effects. (Liz Szabo, CIDRAP, November 19, 2025.) Excellent overview.

* The article, which may be temporarily freely available: Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of Modified mRNA Influenza Vaccine. (D Fitz-Patrick et al, New England Journal of Medicine 393:2001, November 20, 2025.)

Also... About the same time, another article appeared with Phase 2 results for another mRNA vaccine against flu. It is a small trial, with results that are encouraging. A news story for this article: Experimental mRNA flu vaccine shows superior efficacy against symptomatic illness. (Mary Van Beusekom, CIDRAP, November 25, 2025.) This news story links to the article, and to an accompanying editorial.

Posts on flu are listed on the supplementary page Musings: Influenza. The most recent post on the development of mRNA vaccines against flu is listed there for 2023.

November 2025

Ants in your milk?

November 19, 2025

You may get yogurt -- good yogurt.

Four red ants in a small jar of warm milk. Let it sit at a comfortable temperature for a day or so. It will already be moving toward the consistency -- and taste -- of yogurt.

The fermentation is due to the ant ''holobiont'' -- the ant microbiome plus the ants themselves. A new article explores the microbiology and enzymology of ant yogurt. It can be quite complex, with the nature of the product depending on ant details. The article includes testing of ant-milk products at a prominent restaurant.

Why would one explore ant yogurt? It is actually a traditional (though now uncommon) process in some parts of the Balkans. The scientists got the project started with hands-on guidance from a family in Bulgaria.

Caution... Don't just try this without learning more about it. There is a potential issue about ants carrying disease.

* News story: Making yogurt with ants revives a creative fermentation process. (Phys.org (Cell Press), October 3, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Making yogurt with the ant holobiont uncovers bacteria, acids, and enzymes for food fermentation. (Veronica M Sinotte et al, iScience 28:113595, October 17, 2025.) A very readable article, with considerable perspective from various viewpoints, including microbiology and anthropology.

More yogurt: The nutritional value of yogurt? (September 28, 2018).

Great white sharks: a genetic mystery

November 12, 2025

Sharks, like other animals, have two types of genome: the main nuclear genome, and the smaller mitochondrial genome. Interestingly, analysis of the two types of genomes in different shark populations leads to different conclusions about how the populations are related.

Mitochondrial genomes are transmitted only by the females. It is possible that the different patterns between populations could be due to the two sexes having different migration patterns, leading to differences in gene flow. In fact, some observations of the sex-specific migration patterns supported this idea.

A new article does a more extensive genetic analysis of great white shark populations -- and concludes that sex-specific migration does not account for the observed differences in how shark nuclear and mitochondrial genomes spread.

The mystery remains.

* News story: Great white sharks have a DNA mystery science still can't explain. (Science Daily (Florida Museum of Natural History), August 16, 2025.)

* The article: A genomic test of sex-biased dispersal in white sharks. (Romuald Laso-Jadart et al, PNAS 122:e2507931122, August 4, 2025.)

Among shark posts... Eye analysis: a 400-year-old shark (September 3, 2016).

Why horses are rideable: GSDMC

November 5, 2025

In the equid family of animals, only the donkey and horse are commonly ridden by humans. Donkeys are a bit small for much riding, and frankly, wild horses aren't very rideable, either by temperament or anatomy. Horse riding seems to have developed only four thousand or so years ago, relatively recently compared to domestication of most of our familiar animals.

A recent article reports an extensive genetic analysis of horses from around that time. A striking finding is that the frequency of a particular form of the GSDMC gene increased from about 1% to near 100% over just a few hundred years. That is a remarkable increase. It is a sure sign of a major selective force. A selective force part of the development of rideable horses, one might guess.

What does this GSDMC gene do? That's a complex story, but in the immediate context what seems important is that some horses near the Caspian Sea had a rare mutation affecting spinal structure, leading to better rideability, including better endurance. Many early societies had horses for food. But eventually a society that wanted to use horses for carrying things, including people, realized that occasional ones were better -- and they bred them.

The article also provides evidence for mutations affecting horse behavior. But those came earlier. It is the change in GSDMC that best correlates with the increase in riding horses.

* News story: A Single Mutation Made Horses Rideable and Changed Human History -- Ancient DNA reveals how a single mutation reshaped both horses and human history. (Tibi Puiu, ZME Science, August 28, 2025.)

* News story accompanying the article: Evolutionary biology: The rise of rideable horses -- Early horse riders selected a rare mutation in a single gene to enhance rideability. (Laurent Frantz, Science 389:874, August 28 , 2025.)

* The article: Selection at the GSDMC locus in horses and its implications for human mobility. (Xuexue Liu et al, Science 389:925, August 28 , 2025.)

More horse history... Briefly noted... How big were medieval war horses? (January 25, 2022). Links to more.

More about animal domestication: Domestication of rabbits (August 16, 2021).

October 2025

Update: A treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning?

October 30, 2025

Background post: A treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning? (January 13, 2017).

CO does its harm by binding to hemoglobin -- much more tightly than oxygen does. A strategy for dealing with CO is to use another protein, which can bind CO even more tightly, thus removing it from the hemoglobin.

Work such as that in the background post showed some promise with that approach. However, a problem came up. The added protein also bound nitric oxide (NO), and seriously interfered with blood pressure regulation.

A recent article reports progress in dealing with that problem. The secret is to start with an unusual hemoglobin-like protein. It is from bacteria, which use it to sense CO.

The new protein, as modified by the scientists, has shown encouraging results in mouse tests. Good removal of CO, with no effect on blood pressure.

* News stories:

- New Protein Therapy Shows Promise as First-Ever Antidote for Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. (Jon Kelvey, University of Maryland School of Medicine, August 12, 2025.)

- Breakthrough Protein Therapy Emerges as First-Ever Antidote for Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. (Bioengineer, August 12, 2025.) More details, including about the source of the bacterial protein.

* The article: Engineering a highly selective, hemoprotein-based scavenger as a carbon monoxide poisoning antidote with no hypertensive effect. (Matthew R Dent et al, PNAS 122:e2501389122, August 5, 2025.)

Link to background post is at the top of this post.

Record: Most Nobel Prizes to people from one university system in one year?

October 28, 2025

Earlier this month... Four science professors from the University of California won Nobel Prizes. A new record.

Two each were from the Berkeley and Santa Barbara campuses. Two of the four are retired (emeritus).

Add in an alumnus (from San Diego and UCLA), and you get five Nobels to people from the University of California system. Another record.

* News story: UC wins 5 Nobel Prizes in 3 days - and sets a new world record. (Julia Busiek, University of California, October 9, 2025.) Includes the basic Nobel facts, and links to more information. But... see comment, below.

Comment... Sadly, the news story, from the University, goes off to a political rant. A good story, but couldn't that have been separate, rather than clouding the celebration of scientific achievement? A sign of the times.

Berkeley's newest Nobel winner Omar Yaghi was noted in the post Harvesting water from "dry" air (July 1, 2017).

A recent post about Nobel prizes... Briefly noted... Carolyn Bertozzi Nobel prize (October 7, 2022).

Role of thioesters in prebiotic RNA-based protein synthesis?

October 22, 2025

A recent article shows a way that amino acids could have been joined into peptides prior to the development of modern protein synthesis (such as using ribosomes).

The chemistry here centers around the role of thioesters. In short, the scientists shored that small thioesters could have been made under plausible prebiotic conditions, and that the thioesters could then have helped to connect amino acids. The pathway includes attachment of the amino acids to small RNA molecules, thus mimicking the role of transfer RNA.

As always, there is no way to know if such chemistry was actually involved in the development of modern life. However, such work expands the list of known pathways that could have been involved.

Thioesters in modern biology? Most famously, acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA) and such.

* News stories:

- Scientists Recreate a Step That May Have Sparked Life -- Cracking the mystery of life's first proteins. (Amit Malewar, Tech Explorist, September 3, 2025.)

- Thioester RNA Aminoacylation Enables Peptide Synthesis. (Bioengineer, September 5, 2025.) More technical.

* The article (open access): Thioester-mediated RNA aminoacylation and peptidyl-RNA synthesis in water. (Jyoti Singh et al, Nature 644:933, August 28, 2025.)

Another post exploring possibilities for prebiotic synthesis of proteins: Encoding peptides from primordial RNA? (June 6, 2022).

A post about a thioester related to acetyl CoA... A novel enzymatic pathway for carbon dioxide fixation (March 12, 2017).

Sleep and growth hormone

October 15, 2025

It's well known that sleep leads to the production of growth hormone in humans. Little is known about how this happens.

A new article explores the issue at an unprecedented level of detail. It is based on neurophysiological measurements in mice.

A simple summary is that multiple factors stimulate and inhibit production of growth hormone -- and they do so differently during different phases of sleep (such as REM and non-REM). A new finding is that growth hormone ends up stimulating wakefulness. Overall, the work provides a more complete picture of how production of growth hormone during sleep is regulated at the neurological level.

The work here is in mice. Much of how the brain is organized is conserved among mammals. On the other hand, mice sleep quite differently than people; they sleep in many short bursts, a few minutes at a time. The current work should be taken as a starting point, using a convenient animal model. Further work will explore how well the findings here translate to humans. In principle, a batter understanding of how sleep works could lead to improved medical treatments for sleep disorders.

* News stories:

- Sleep strengthens muscle and bone by boosting growth hormone levels. UC Berkeley researchers discover how -- Growth hormone released during sleep is critical not only for childhood growth but also for adult metabolism. A new study reveals the complex brain circuits involved, offering fresh insights into health and fitness. (Robert Sanders, University of California, Berkeley, September 8, 2025.)

- The Sleep Secret: How Growth Hormone Fuels Rest, Then Pushes You Awake. (Study Finds, September 8, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Neuroendocrine circuit for sleep-dependent growth hormone release. (Xinlu Ding et al, Cell 188:4968, September 4, 2025.)

More about growth hormone in mice: Olfaction and obesity? (July 18, 2017).

A recent post about sleep: Is it worthwhile to sleep for four seconds? (February 20, 2024).

Measuring the temperature of ultra-hot atoms -- and uncovering a new way to not melt gold

October 8, 2025

Scientists recently reported heating a piece of gold to 19,000 Kelvins -- without it melting. The standard melting point for gold is about 1,300 Kelvins.

It's an interesting paper for multiple reasons. Simply doing it was quite a technical feat. And the result was surprising -- especially to those who thought they understood super-heating.

Part of the procedure was straightforward: heat a piece of gold foil with a laser. The challenge is determining the exact state of the gold, including temperature (T), on an atom-by-atom basis. This was done by X-ray analysis, with a sophisticated X-ray system. The key was measuring the energy of individual X-rays, and relating that to the temperature of the specific atom that X-ray had encountered.

That analysis led the scientists to conclude that the Au atoms were still in the ordered arrangement of the solid -- but were at temperatures as high as 19,000 Kelvins.

So, it is superheated. What's the problem? The problem is that, four decades ago, physicists developed a theoretical analysis that predicted that the maximum possible temperature for superheating was about three times the melting point (in Kelvins). At that T there would be an entropy catastrophe, which would forbid having a superheated material at any higher T.

The current work showed superheated material at nearly five times the maximum possible T. That is, the observed experimental result is theoretically impossible.

Such contradictions can be the starting point for new developments. At this point, no one knows how to resolve the contradiction.

One idea that the scientists offer is that the gold does not melt because the heating is so fast that the atoms have not had enough time to separate. The heating rate was about 1015 Kelvins per second.

* News stories:

- The limit does not exist: Superheated gold survives the entropy catastrophe -- Researchers taking the first-ever direct measurement of atom temperature in extremely hot materials inadvertently disproved a decades-old theory and upended our understanding of superheating. (Erin Woodward, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, July 23, 2025.)

- Superheated Gold Defies 'Entropy Catastrophe' Limit, Overturning 40-Year-Old Physics -- Physicists superheated gold to 14 times its melting point, disproving a long-standing prediction about the temperature limits of solids. (Clara Moskowitz, Scientific American, July 23, 2025.) Includes an alternative suggestion about what happened -- helping to make clear that it is a mystery -- for now.

* The article (open access): Superheating gold beyond the predicted entropy catastrophe threshold. (Thomas G White et al, Nature 643:950. July 24, 2025.)

Among posts about gold... Prospecting for gold -- with help from the little ones (March 1, 2013). Includes a list of gold-related posts.

More X-ray work from SLAC: Stanford Linear Accelerator recovers 18th century musical score (June 22, 2013). Links to more.

September 2025

A defined fermentation process that could improve quality control in making chocolate

September 30, 2025

Chocolate is made by a complex process that includes a fermentation step. This was introduced in the background post listed below. A new article provides an extensive analysis of how variations in the fermentation process affect the nature of the chocolate.

The work started by analyzing the microbes in various chocolate fermentations, leading to an apparent association of certain microbes with certain features of the product. This led to the development of defined microbial mixes. Analyses of test fermentations using these mixes showed that the products had the expected features, as judged by chemical analysis and taste testing.

The work may lead to the development of starter cultures, which could be used at the start of the fermentation step. Such starter cultures help to get greater consistency in the product. They are commonly used in other fermentations, such as for beer and cheese, but have not been used for chocolate. Of course, the use of starter cultures allows for the development of different starter cultures to get products with different features. This is of interest in making specialty chocolates.

* News stories. Both include some discussion of the background about chocolate fermentations.

- New research ferments the perfect recipe for fine chocolate flavor. (Phys.org (University of Nottingham), August 18, 2025.)

- These Lab-Controlled Microbes Can Make Any Chocolate Taste Gourmet. From hints of citrus to caramel, premium chocolate's complex flavors derive from fermenting microbes on cocoa bean farms -- and a new study suggests they can be grown on demand in the lab. (Lauren J Young, Scientific American, August 18, 2025.)

* The article (open access): A defined microbial community reproduces attributes of fine flavour chocolate fermentation. (David Gopaulchan et al, Nature Microbiology 10:2130, September 2025.)

Background post: Better chocolate? Use better yeast? (May 3, 2016). Links to more.

Using onions to improve solar cells

September 23, 2025

A bit old, so just briefly...

Solar cells typically operate using the visible part of the spectrum.

The higher-energy UV light can actually damage the cells. Therefore, filters are included to reduce the UV getting to the sensitive components. Plastic materials, derived from fossil fuels, are common.

A recent article reports trying a variety of materials as UV filters for solar cells. The titles below (news story and article) tell you what they tried -- and who won. Of particular interest, the winning material not only filleted very well, but was more durable than the traditional materials.

* News story: A New Solar Panel Shield Made From Onion Peels Outlasted Industry Plastics in Tests -- Natural dye from discarded onion peels outperforms fossil-based UV filters in durability and performance. (Tudor Tarita, ZME Science, September 7, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Sustainable Nanocellulose UV Filters for Photovoltaic Applications: Comparison of Red Onion (Allium cepa) Extract, Iron Ions, and Colloidal Lignin. (Rustem Nizamov et al, ACS Applied Optical Materials. 3:664, February 24, 2025.)

The section of my page Introduction to Organic and Biochemistry Internet resources for Energy resources includes some posts on solar cells.

Previous posts about onions: none. Well, there is Why does a durian smell so bad? (February 14, 2017).

Sugar in drinks vs sugar in solid foods: Do they have different effects?

September 17, 2025

That title may strike you as odd. A gram of sugar is a gram of sugar. It yields some amount of energy (some number of Calories). Why would the form of the source matter?

A recent article looks at the correlation between sugar consumption and the incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D). The article provides a meta analysis of 29 previously published studies. The statistical analysis suggests that there may be an effect of the form of the sugar. Liquid sugar (sugar in drinks) correlates with an increase in the incidence of T2D; solid sugar does not.

Want to see some numbers? Two of the figures summarizing the statistics in the article are included in the KSL news story listed below. Figure 1 shows the magnitude of the effect, with confidence limits, for various sugar sources. Figure 2 shows dose-response results. If you go to the data, focus on SSB = sugar-sweetened beverages, such as soft drinks. That sugar source shows the largest effect.

How could this be? At this point, we do not know. One can imagine various possibilities. For example... The rate of sugar consumption may matter. The accompanying ingredients may matter. Further work is needed.

The authors caution that their work has limitations. The studies they analyze were not controlled studies on this issue. What the work here does is to suggest an effect; we now need further studies focused on this point to see how well it holds up.

* News stories:

- Drinking Sugar May Be Far Worse for You Than Eating It, Scientists Say. Liquid sugars like soda and juice sharply raise diabetes risk -- solid sugars don't. (Tibi Puiu, ZME Science, June 11, 2025.)

- 'The nutritional villain': BYU study says drinking sugar poses higher risk for diabetes than eating it. (Gabriela Fletcher, KSL, June 2, 2025.) This news story includes two figures from the article, as noted above. (KSL? A major radio station, in Salt Lake City, Utah -- not far from the lead university for the article.)

* The article (open access): Dietary Sugar Intake and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Risk: A Systematic

Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. (Karen A Della Corte et al, Advances in Nutrition 16:100413, May 2025.)

Among many posts on nutritional issues with sugars... Fructose; soft drinks vs fruit juices (November 7, 2010). Links to more.

I have listed this post on my page Internet resources: Biology - Miscellaneous under Nutrition; food and drug safety.

I have also listed this post on my page Organic/Biochemistry Internet resources under Carbohydrates.

The genetics of orange cats

September 11, 2025

Some cats have orange fur -- and the common pattern is different in male and female cats. Orange is an unusual color for mammalian fur, and there is no other case known of it being sex-linked.

A recent article uncovers the gene that leads to orange cat fur.

It's a complicated story, and we won't try to get all the details here. Briefly, the mutation affects gene regulation, and affects the ratio of two forms of melanin. It is distinct from other known mechanisms of melanin regulation.

The orange gene is on the X-chromosome. Male cats, with one X chromosome, can be fully orange. However, in females, orange fur is usually found in small, random patches. That happens because of the phenomenon of X-chromosome inactivation. In female mammals, only one X chromosome is active in an individual cell. Typically, patches of cells will use the same X, reflecting inheritance of the active vs inactive state. Orange patchiness in the fur of female cats is a visible manifestation of the phenomenon of X-chromosome inactivation.

Female cats with patches of orange fur are known as calico or tortoiseshell.

Female cats can be fully orange if they are homozygous for the orange gene.

* News story: Geneticists have finally solved the mystery of Garfield's orange coat. (Lluís Montoliu, The Conversation, December 4, 2024.) Features a picture of the most famous orange cat. (Need I explain that?) Discusses both articles, as posted as pre-prints. Good overview of how the orange gene works.

* Two articles, together in the journal:

- A deletion at the X-linked ARHGAP36 gene locus is associated with the orange coloration of tortoiseshell and calico cats. (Hidehiro Toh et al, Current Biology 35:2816, June 23, 2025.) This one is open access.

- Molecular and genetic characterization of sex-linked orange coat color in the domestic cat. (Christopher B Kaelin et al, Current Biology 35:2826, June 23, 2025.)

More about X-chromosome inactivation: X-chromosome inactivation in males -- in cancer (February 6, 2023). Links to more.

More cat genetics... The previous post, just below: The genetics of cat purring (September 9, 2025).

The genetics of cat purring

September 9, 2025

You may know that some cats are more talkative than others. A recent article explores the genetics behind this phenomenon.

The work focused on the androgen receptor (AR) gene. One typically thinks of androgens, such as testosterone, as male hormones. However, in both sexes, the adrenal glands make small amounts of androgens. It is known that the AR gene is involved in behavior in both males and females (of various mammalian species).

In this work, the behavior of 280 house cats was assessed. The cats were all mixed-breed, and had been spayed or neutered. The assessment was done by having the cat owners fill out the Feline Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire (Fe-BARQ).

An interesting aspect of the AR gene is a small repeated sequence, which may occur 15-22 times.

The main finding is that the talkativeness of a cat correlates with the length of that repeated sequence in the androgen receptor gene. Cats with short repasts are noisier than cats with long repeats.

The scientists also compared different types of cats. The big cats are noisy -- perhaps important to their survival in the wild. And they have short repeats. Among house cats, pure breds are quieter, and have longer repeats. It seems that man has bred cats to be quieter.

How variation in the androgen receptor affects cat talkativeness is unknown.

Variation in that repeat sequence in the AR gene has previously been linked to aggression in dogs and fear responses in camels.

Humans? The article mentions two references suggesting an effect of this genetic variation on adolescent boys.

* News stories:

- The purrfect gene. (Kyoto University, May 29, 2025.)

- Chatty Cats: Rescues May Be Genetically Wired To Be More 'Talkative'. (Study Finds, June 2, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Association between androgen receptor gene and behavioral traits in cats (Felis catus). (Yume Okamoto et al, PLoS One 20:e0324055, May 28, 2025.) The Introduction is a nice overview of what we know about purring, and more broadly about the genetics of behavior in cats and dogs. In fact, the whole article may make good reading; skip over the data details if you want.

A recent post on cat behavior: Briefly noted... Do cats know the names of their house-mates? (June 1, 2022).

More cat genetics... The next post, just above. The genetics of orange cats (September 11, 2025). Added September 11, 2025.

Using bacteria to leach valuable metals, including rare earths, from rocks -- and to capture atmospheric carbon

September 4, 2025

The bacterium Gluconobacter oxydans oxidizes glucose to gluconic acid; that is the basis of its name. Do that with rocks around, and many metal ions will be solubilized. Of particular interest, there is good solubilization of many valuable rare earth elements (REE). Further, the conditions favor the capture of CO2 from the air. The first part of that was introduced in the background post listed below.

A team of scientists has been studying all that. They have examined which bacterial genes promote the processes for dissolving metal ions and for capturing CO2. And they have developed bacterial strains with improved properties.

Could this become a practical process? The authors have formed a company to try to implement it.

* News story, for all the articles listed below: Microbes that extract rare earth elements also can capture carbon. (Krisy Gashler, Cornell University, June 4, 2025.)

* Three recent articles, from the same lab (all in open access journals). I might suggest you start by reading the three abstracts.

1) Bio-accelerated weathering of ultramafic minerals with Gluconobacter oxydans. (Joseph J Lee et al, Scientific Reports 15:15134, April 30, 2025.)

2) Direct genome-scale screening of Gluconobacter oxydans B58 for rare earth element bioleaching. (Sabrina Marecos, Communications Biology 8:682, April 30, 2025.)

3) High efficiency rare earth element bioleaching with systems biology guided engineering of Gluconobacter oxydans. (Alexa M Schmitz et al, Communications Biology 8:815, May 27, 2025.)

Background post: Extraction of rare-earth metals: a bacterial assist (February 8, 2022).

Another approach to recovering REE: Briefly noted... Extracting rare earth elements from coal fly ash: use of various supercritical solvents (April 1, 2023).

More on CO2 capture: Precipitating CO2 from air (July 30, 2022).

This post is listed on my page Introductory Chemistry Internet resources in the section Lanthanoids and actinoids.

August 2025

Retraction: "NASA: Life with arsenic"

August 28, 2025

It's an odd story. A 15-year-old article has been retracted. An article the world first learned about from a strange NASA press conference. It was an interesting -- and controversial -- science story. The extreme claims of the article were debunked long ago; in fact, by the time the article appeared in print, it was accompanied by several "technical comments" critiquing the work.

Why retract it now? There is no new science, no new information. There is some evolution of retraction policy. The retraction itself has become the center of controversy. The journal explicitly notes that there is no claim of misconduct -- just sloppiness.

At this point, this is mainly a story of science policy.

For more, see the original post: NASA: Life with arsenic (December 7, 2010). Two follow-up posts are linked there.

Genetic analysis suggests there are four different types of autism, with different genetic features

August 26, 2025

Autism is heterogeneous -- so heterogeneous that the simple term has largely been replaced by more complex terms such as autism spectrum disorder.

A new article offers a new approach to sorting out the complex puzzle of autism. The scientists fed data on over 5000 people with autism to a computer. The data included genomes, but also data on about 200 behavioral traits associated with autism. That combination of genotype and phenotype data was central to the study. The question was not simply to look for genes associated with "autism". Instead, the question was to find genes associated with traits -- or combinations of traits.

The computer analysis suggests that there are four types of autism, each characterized by a distinct set of traits and genes. We'll leave the details for now; they are quite complicated. What's important is that this seems to be a major step toward dissecting the complexity of "autism". Further work will test and refine the framework suggested here.

* News stories:

- Scientists Have Identified 4 Distinct Types of Autism Each With Its Own Genetic Signature -- Researchers uncover hidden biological patterns that may explain autism's vast diversity. (Tudor Tarita, ZME Science, August 8, 2025.)

- Major autism study uncovers biologically distinct subtypes, paving the way for precision diagnosis and care. (Molly Sharlach, Princeton University, July 9, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Decomposition of phenotypic heterogeneity in autism reveals underlying genetic programs. (Aviya Litman et al, Nature Genetics 57:1611, July 2025.)

A previous post on autism genes: Can we make sense of the many genes involved in autism? (January 16, 2015).

My page for Biotechnology in the News (BITN) -- Other topics includes a section on Autism. It includes a list of related Musings posts. Some of them are about genetic issues.

Developing a gut microbe that protects against a toxic form of mercury

August 20, 2025

Some seafood contains significant levels of methyl mercury, a particularly toxic form of mercury. Those who consume such contaminated seafood regularly, because of the local environment, are at particular risk. Further, the risk is of special concern for fetuses of mothers who consume Hg-contaminated seafood.

A recent article offers an approach to dealing with consumption of food containing methyl mercury.

The idea is simple. There are bacteria that are quite resistant to methyl mercury. They contain an enzyme system that detoxifies it. The scientists added the genes for that enzyme system to a type of bacterium that is common in the human gut. The modified bacteria made the enzyme, and were indeed resistant to methyl mercury.

The bacterium used is Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. (Yes, that species name consists of the names of three Greek letters.)

The enzyme system liberates the mercury of methyl mercury as free (elemental) mercury. There are two steps, which can be summarized...

1. CH3-Hg --> CH4 + Hg2+

CH3-Hg is also referred to as "MeHg", using Me for methyl.

2. Hg2+ --> Hg

The modified bacteria were then tested in an animal model, using mice. The bacteria were added to the gut microbiome of the mice. Such mice were then given a dose of methyl mercury, or fed seafood with a known high level of the toxic mercury. Over a variety of such tests, the mice with the modified bacteria accumulated less Hg in the intestines -- and in other tissues, including the brain. A test with pregnant mice showed that the modified bacteria in the mother's gut reduced Hg in the fetal tissues.

The work is encouraging, and the authors are thinking about how to move on to testing in humans. The idea is that the modified bacteria could be administered as a probiotic. They would provide some protection for those who eat food with high levels of methyl mercury. Targeting pregnant women, to protect the fetuses, might be of particular interest.

* News stories:

- Designer microbe shows promise for reducing mercury absorption from seafood -- UCLA and UCSD research suggests a probiotic could one day increase the benefits of eating fish. (Holly Ober, UCLA, May 1, 2025.)

- Breakthrough Research: Engineered Gut Microbes Offer New Hope for Reducing Mercury Absorption from Seafood -- The Mercury Dilemma: Balancing Seafood Benefits with Toxin Exposure. (Forward Pathway, May 3, 2025.) Long, with a casual style. But quite good. It goes beyond the current article to discuss other ideas about microbiome modification. (Ok to read those later parts at another time.)

* The article: An engineered gut bacterium protects against dietary methylmercury exposure in pregnant mice. (Kristie B Yu et al, Cell Host & Microbe 33:621, May 14, 2025.)

More Hg: Mercury pollution from Arctic melting (February 19, 2019).

Another post that might lead to a probiotic: Accumulation of PFAS ("forever chemicals") by bacteria in the human gut (August 13, 2025). The previous post, just below.

Accumulation of PFAS ("forever chemicals") by bacteria in the human gut

August 13, 2025

Perfluoro chemicals (PFAS, organics with all the C-H replaced by C-F) are persistent; that is the basis of their nickname "forever chemicals". There is increasing evidence that they are harmful.

A recent article shows that they are accumulated by bacteria in the human gut.

Exploration of individual types of bacteria showed that they vary widely in their ability to accumulate PFAS. The basis of the difference is not understood. (In one case, the scientists showed that bacteria actively excrete the PFAS. Mutations in an efflux gene led to higher accumulation.)

Tests with germ-free mice showed that addition of bacteria led to increased removal of PFAS in the feces. Bacteria characterized as good accumulators had a greater effect than those that were poor accumulators, at least when normalized by bacterial mass. (The good accumulators colonized the mice more poorly. It is not clear what the net result was.)

Let's assume that the basic findings, as summarized above, are significant. What is the practical significance? We can envision probiotics with increased PFAS accumulation. Oral intake is only one route of exposure to PFAS. Does PFAS accumulation by gut bacteria have any benefit to the person? What are the downstream environmental effects? These points are not obvious at this point, but can be studied in further work.

An intriguing finding.

* News stories:

- Your gut has a secret weapon against 'forever chemicals': microbes. (Mihai Andrei, ZME Science, July 3, 2025.)

- Gut microbes could protect us from toxic 'forever chemicals'. (University of Cambridge, July 1, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Human gut bacteria bioaccumulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. (Anna E Lindell et al, Nature Microbiology 10:1630, July 2025.) Caution...The article is not easy reading. The first sentence is quite mysterious; beyond that, it varies. Be patient if you try to work through the article.)

Also see: Getting rid of "forever chemicals" (perfluorinated organic acids) (October 25, 2022). Chemical processing.

Another post that might lead to a probiotic: Developing a gut microbe that protects against a toxic form of mercury (August 20, 2025). Added August 20, 2025. Next post, just above.

Could you tame hot peppers by adding an anti-hot substance?

August 6, 2025

Chili peppers are noted for their "hot" flavor, also called pungency or spiciness. That feature is due to a chemical called capsaicin (and to some closely related chemicals). It is known how the hot flavor is sensed. Capsaicin binds to and activates a receptor whose "normal" job is to sense heat. Since the chemical activates a heat receptor, we sense the chemical as heat.

What else is in the peppers? Scientists recently reported an extensive analysis of the "flavorome" of several types of chili peppers (genus Capsicum). The idea was to extract chemicals from the peppers, and test them. The testing was done using the "half-tongue test", with trained taste testers. Two samples were placed on the tongue, one on each side. The tester was asked to report which sample was hotter.

Let's say we want to test a new chemical X. We want to compare with the bona fide "hot" (capsaicin, C). One test might be to compare X and C, with one on each side of the tongue. But another test might be to put them together, for example, C compared to C + X.

The testing led to three chemicals with a novel property: C + X was judged less hot than C alone. That is, X seems to be an anti-hot (or anti-spicy) substance, reducing the hotness of C. Interestingly, all three such anti-hot chemicals were themselves tasteless.

How might that work? The scientists have no information on the mechanism at this point. But one simple possibility is that X might bind to the receptor very well, even better than C, but not activate it. An X with such properties would reduce the amount of C bound, but not itself create any taste response. (We also need to assume that it does not activate any other taste receptor.)

Might this be a useful food condiment, to adjust the flavor of hot peppers? That is beyond the current article, but the scientists are aware of the possibility. (The work was supported by the Flavor Research and Education Center at the Ohio State University.)

You may have heard of Scoville heat units (SHU) for measuring the hotness of chili peppers. It is based on chemical analysis, and uses the levels of two major "hot" chemicals. The finding of anti-hot chemicals disrupts the Scoville scale as a measure of overall hotness.

* News story: Scientists Found 'Anti Spicy' Compounds That Make Hot Peppers Taste Milder -- One day, an anti-spicy sauce could make your food less harsh. (Tibi Puiu, ZME Science, May 15, 2025.)

* The article: Identification of Chili Pepper Compounds That Suppress Pungency Perception. (Joel Borcherding et al, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 73:12917, May 28, 2025)

Among many posts on sensory receptors...

* How a cork causes an off-flavor in a beverage (October 21, 2013). This may be another example where the primary effect is actually an inhibition.

* What does blue light smell like? (July 18, 2010).

July 2025

N6: A new form of nitrogen

July 31, 2025

N-=N+=N-N=N+=N-

It's the first stable form of (neutral) nitrogen found since the description of ordinary N2 back in 1772. N3 and N4 have been reported, but only transiently. Even here, most work was done at very low temperatures (77 K or lower).

The extreme stability of ordinary N2, N≡N, looms over the story. This new N6, too, quickly breaks down at room temperature -- to 3 N2. The estimated lifetime at 298 K (25 °C) is about 40 milliseconds. But at 77 K, that number goes to over a hundred years, "stable" in a practical sense.

How did the scientists make this hexanitrogen? Rather simply... A metal azide salt (AgN3) was converted to a covalent azide (such as ClN3). Further reaction with AgN3 leads to N6 (+ AgCl), by the coupling of the two azide groups. (That coupling gives the single bond in the middle; see the structure at the top of this post. Also note that the two middle N atoms each have a lone pair of electrons. Those two atoms have tetrahedral electron geometry.)

There is an intriguing idea behind this work -- beyond simply the curiosity of making a novel chemical. What if we could use a fuel, with the only waste product being ordinary N2 -- non-toxic and already abundant? The N6 made here illustrates the idea. The synthesis involves toxic chemicals, but using the fuel would not add toxic gases to the air. This N6 is not likely to be a practical fuel, but perhaps it is a start.

* News story: Chemists produce hexa-nitrogen for the first time - the most energy-rich substance ever formed. (Peter R Schreiner, chemeurope.com, June 17 , 2025.)

* The article (open access): Preparation of a neutral nitrogen allotrope hexanitrogen C2h-N6. (Weiyu Qian et al, Nature 642:356, June 12 , 2025.) (The C2h in the name there is not about the composition. Instead, it describes the symmetry of the molecule.)

Unusual nuclear chemistry involving nitrogen: Nitrogen-9 and 5-proton decay (January 16, 2024).

An element with many allotropes: A new form of carbon -- hard enough to scratch diamond (March 1, 2022). Links to more.

Follow-up: A laser-based missile-defense system to bring down mosquitoes

July 29, 2025

See the update note at the end of the post A laser-based missile-defense system to bring down mosquitoes (May 18, 2010).

Initial studies of an exotic liquid: carbon

July 23, 2025

There is probably liquid carbon in the interior of some astronomical bodies, but on Earth, the stuff is pretty much unknown. At ordinary pressures, C does not melt; it goes directly from the solid state to a gas -- at very high temperatures. Further, theories about the nature of liquid carbon are incomplete and inconsistent.

The triple point of a substance is where all three phases (g, l, s) can exist together. At pressures below that of the triple point, there is no liquid phase. For C, the triple point is about 100 atmospheres pressure (about 107 Pa) and 4600 Kelvins.

A recent article exploring the nature of C(l) is a technical breakthrough. The C is heated with a laser, and the resulting material is studied with X-ray pulses. The article contains a few seconds of data.

Pictures of liquid carbon? No. Interesting properties? Well, it seems most common that each C atom in the liquid is surrounded by four other C atoms.

Some readers may be surprised to learn how little is known about liquid carbon. In that context, the new article is of interest simply because they did it.

* News story: Structure of liquid carbon measured for the first time. (HZDR, May 21, 2025.) HZDR = Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf.

* "Research briefing" from the journal: Liquid carbon formed using a high-energy laser. (Nature, June 11, 2025; online only.) Includes comments from the lead author, and more.

* The article (open access): The structure of liquid carbon elucidated by in situ X-ray diffraction. (D Kraus et al, Nature 642:351, June 12, 2025.)

I have listed this post on my page Organic/Biochemistry Internet resources in the section on Introduction; alkanes. It is part of the story of carbon.

The role of dietary iron in sex determination in mammals

July 16, 2025

One of the first things people learn about sex determination in mammals is that the Y chromosome determines maleness. The reason for this is that a gene known as Sry, normally located on the Y chromosome, turns on the male development pathway.

A new article adds another piece of the story. The proper functioning of Sry requires iron (Fe2+). This works through an epigenetic effect, involving methylation of regulatory proteins on the Sry gene. The authors went on to show that if mouse mothers were iron-deficient, some of their XY offspring developed as females, at least partially.

The Fe2+ is needed for a demethylase enzyme to be active. That enzyme removes methyl groups from histones on the Sry gene, allowing it to be active. At low iron levels, the demethylase is inactive, thus leaving the histones methylated -- and Sry inactive. That is the basis of the role of iron in sex determination.

The work in the new article falls into two general types. One is showing that pathway: how iron affects Sry. The second is showing that it is actually relevant in vivo.

This is the first case where an environmental effect on sex determination has been shown in a mammal. (Such environmental effects are well known in other animals, including fish and reptiles.) It illustrates, once again, that biology is more complex than we usually think. The Y chromosome plays a key role in male development, but there is complexity in how it acts.

Is this relevant to humans? At this point, there is no information available on that question. The work here was entirely with mice. However, we should take seriously the possibility that it is relevant to humans. The basic biochemistry of Sry is about the same in mouse and human. Iron deficiency at the level studied here is common in human populations. So it is important to pursue what was found here for mice to see how it applies to humans.

* News stories. All of the following stories make useful contributions to understanding the complex article at hand. Reading any one of them is good, but the set adds considerably more.

- Maternal iron deficiency disrupts embryonic sex determination in mice. (News-Medical.net (University of Osaka), June 11 2025.) Brief but useful overview, from the lead university.

- Iron Deficiency Can Flip The Genetic Switch That Determines Sex, Turning Male Embryos into Female -- Researchers show maternal iron levels can override genetic sex determination in mice. (Tudor Tarita, ZME Science, June 9, 2025.)

- Maternal Iron Deficiency Triggers Sex Reversal. (Bioengineer, June 4, 2025.)

- Iron Deficiency Can Cause Sex Reversal in Mouse Fetuses -- Pregnant mice without enough iron can have genetic male fetuses with ovaries. (Ari Berkowitz, Psychology Today, June 16, 2025.) Includes some discussion of what is known about variations in sexual development in humans. Again, we note that, for now, we know nothing about the possible implications of the current article for humans.

* News story accompanying the article: Development: Iron deficiency affects

development of the testes -- In mice, a lack of maternal iron impairs an iron-dependent enzyme that activates the male sex-determining gene, causing some XY embryos to develop ovaries. (Shannon Dupont & Blanche Capel, 643:45, July 3, 2025.) Added July 17, 2025.

* The article: Maternal iron deficiency causes male-to-female sex reversal in mouse embryos. (Naoki Okashita et al, Nature 643:262, July 3, 2025.)

The Sry gene was mentioned in the post On his right side, he is female (April 24, 2010). That post is about chickens -- and an unusual situation there.

An example of an environmental effect on sex determination: Twenty percent of the females are genetic males (October 6, 2015).

"3D printing" inside the body, using ultrasound

July 9, 2025

Want to build a structure inside the body? Inject a precursor. Then activate it using ultrasound, guided precisely by imaging. The activated precursor reacts, forming the intended structure.

The descriptions get bogged down a bit by the terminology or analogy. I'm not sure it helps to start with your notion of 3D printing. But the approach is logical -- and it works. Is it a form of "3D printing"? Sure, why not? The injected precursor is an "ink" (or "bioink"). It is the ultrasound that provides the control.

Musings has noted other work on "printing" body parts. What is new here is the complexity of the process -- inside the body. The key development in the article is the use of ultrasound, which can penetrate into the body, to control the process. The ultrasound provides localized heating, which releases cross-linkers that polymerize the main "ink" material.

The technique is called deep tissue in vivo sound printing (DISP). So far, it has been tested to repair damage to a mouse's bladder and a rabbit's leg muscles. It avoids surgery, and is faster. The authors also suggest that the method could be used for localized drug delivery, with the timing controlled by doses of ultrasound.

* News story: This Injectable Ink Lets Doctors 3D Print Tissues Inside the Body Using Only Ultrasound -- New 3D printing technique makes it possible to heal injuries and damaged tissues from inside without surgery. (Rupendra Brahambhatt, ZME Science, May 22, 2025.)

* News story accompanying the article: Replicating a tissue with sound waves -- Ultrasound waves can penetrate thick tissues and print implants on demand inside a body. (Xiao Kuang, Science 388:588, May 8, 2025.)

* The article: Imaging-guided deep tissue in vivo sound printing. (Elham Davoodi et al, Science 388:616, May 8, 2025.)

There is more about replacement body parts on my page Biotechnology in the News (BITN) for Cloning and stem cells. It includes extensive lists of related Musings posts.

Some items listed there (in list 1) involve 3D printing, such as 3D printing of human tissues: the ITOP (May 24, 2016).

More ultrasound: An ultrasound device you can wear (September 17, 2022). Links to more.

Microplastics from glass bottles?

July 2, 2025

Yes, indeed.

A new article reports testing a wide range of drinks sold in France for microplastics. Results vary widely, as might be expected. But the striking result was that beverages sold in glass bottles generally had the highest levels of microplastics -- by far.

Observation of the plastics from glass bottles suggests that they come from the paint on the bottle caps.

Interesting finding. Maybe this is a solvable problem.

* News story: The caps of glass bottles contaminate beverages with microplastics. (ANSES (Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l'alimentation, de l'environnement et du travail), June 20, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Microplastic contaminations in a set of beverages sold in France. ( Iseline Chaïb et al, Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 144:107719, August 2025.)

Also see: History of plastic -- by the numbers (October 23, 2017). This is a general post on plastics, with links to much more, including some posts on microplastics.

June 2025

On egg-dropping

June 25, 2025

Let's just jump in and look at some data...

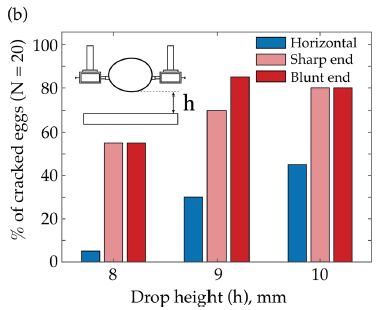

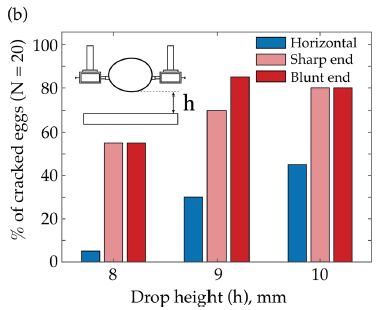

|

In each test, 20 eggs were dropped -- in a defined orientation and at a defined height. The bar height shows the percentage of cracked eggs for each test.

For the group of bars at the left, the eggs were 8 mm above the surface -- as measured to the bottom of the egg. The blue bar, for eggs held horizontally, shows that 5% (1 egg) cracked. The two reddish bards, for eggs held vertically, shows that about half cracked upon falling.

The pattern was similar for eggs dropped from other heights.

This is Figure 2b from the article.

|

The conclusion is that eggs dropped horizontally are less likely to crack.

More detailed work suggests that, in the context of a free fall, the horizontal eggs are better at absorbing the energy. They deform rather than break.

* News stories:

- MIT engineering students crack egg dilemma, finding sideways is stronger -- A new study reveals why eggshells are stronger on their sides, overturning a popular science belief. (Stephanie Martinovich, MIT, May 8, 2025.)

- An Egg Survives Better When Dropped on Its Side. (Michael Schirber, Physics 18:100, May 9, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Challenging common notions on how eggs break and the role of strength versus toughness. (Antony Sutanto et al, Communications Physics 8:182, May 8, 2025.)

Also see: What is the proper shape for an egg? (September 18, 2017).

A better way to make hydrogen-6

June 18, 2025

The H-6 nucleus has proven difficult in both theory and experiment. It is hard to make. And it doesn't hang around long: half-life is 294 yoctoseconds (about 3x10-22 s).

The H-6 nucleus consists of 1 proton (which defines it as hydrogen) and 5 neutrons. It has the second highest ratio of neutrons to protons of any known nucleus. Only the even-more-obscure H-7 nucleus has a higher ratio. (Imagine a uranium nucleus with over 450 neutrons!)

A new report develops a new approach to making -- and detecting -- H-6. It worked; the scientists made about one H-6 nucleus a day for a month.

The production system is based on making H-6 from Li-7, the common lithium nucleus. Doing that requires losing two protons, but only one neutron. Effectively, one of the protons of the Li nucleus is converted to a neutron. The process is initiated by an electron beam.

The detection system is based on combining detectors, to record three products of the event: the emitted proton, a pion by-product, and the scattered electron. The energy of each of those is measured, allowing calculation of the ground-state energy of the H-6 product nucleus.

Why do this? Once again, the big idea is to better understand the limits of atomic nuclei. The new work gives the scientists an improved measurement of the energy level of the H-6 nucleus. That will guide further theoretical work.

* News story: New method to produce an extremely heavy hydrogen isotope at the Mainz Microtron accelerator MAMI -- Production and measurement of the extremely neutron-rich hydrogen isotope 6H achieved for the first time in an electron scattering experiment. Result shows stronger than expected interaction between neutrons within the nucleus. (Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, April 30, 2025.) Excellent overview.

* The article: Measurement of 6H Ground State Energy in an Electron Scattering Experiment at MAMI-A1. (Tianhao Shao et al, Physical Review Letters 134:162501, April 22, 2025.) Very technical, with extensive discussion of the uncertainties.

Another unusual nucleus: Nitrogen-9 and 5-proton decay (January 16, 2024).

More about hydrogen: Hydrogen gas as an anti-aging agent? (January 24, 2024).

This item is listed on my page Internet resources: Introductory Chemistry under Nuclei; Isotopes; Atomic weights.

Breaking latency of HIV, using a technology related to mRNA vaccines

June 11, 2025

There are excellent anti-viral drugs to treat HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). But they are not cures. Stop the drugs and the active infection resumes. Why? HIV is a retrovirus; it has an RNA genome, and it integrates a DNA copy of itself into the host genome. It tends to be silent there, but occasionally it pops out, initiating a new active infection. Curing HIV would seem to require eliminating the latent infection, the virus reservoir in the host genome.

The likely approach to eliminating the latent infection is to activate it -- completely. We know how to treat the resulting active infection, And if we really activated the entire latent infection, there would be nothing left.

A new article reports a major step toward making that work. The idea is to insert a protein into the cells carrying the latent virus. The protein is designed to activate the latent HIV. How did they get the protein into the cells? By wrapping its mRNA in a fat droplet designed to be taken up by the type of cell that carries the latent HIV.

It worked. Very well. In cell culture. It's now time to move on and try to translate the finding to animal models.

Does the approach sound familiar? It is related to how mRNA vaccines are made. The work here is not about a vaccine; it is about a treatment. But it shares technology with the mRNA vaccines, in developing ways to deliver mRNA to cells.

In a narrow sense, this article is about a development in the delivery of mRNA into cells. It may be a step toward a cure for HIV, but there is much more to be done. It may also be possible to extend the work to deal with other viruses, such as herpes viruses, in their latent phase.

* News stories:

- Breakthrough in search for HIV cure leaves researchers 'overwhelmed' -- Exclusive: Melbourne team demonstrates way to make the virus visible within white blood cells, paving the way to fully clear it from the body. (Kat Lay, The Guardian, June 5, 2025.)

- Efficient mRNA Delivery Reactivates Latent HIV in T Cells. (Bioengineer.org, May 29, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Efficient mRNA delivery to resting T cells to reverse HIV latency. (Paula M Cevaal et al, Nature Communications 16:4979, May 29, 2025.)

Previous post about HIV: Briefly noted... A mutation that makes COVID worse protects against HIV (March 9, 2022).

My page for Biotechnology in the News (BITN) -- Other topics has a section on HIV. It includes a list of related posts.

That page also has a section on Vaccines (general). The list of Musings posts there includes some on mRNA vaccines.

Color vision: Five people have now seen the color olo, thanks to Oz

June 4, 2025

Color vision in humans makes use of three types of photoreceptors, each sensitive to a different range of light. The brain collects the data from the three sets of photoreceptors, and interprets the color.

Oz is an instrument designed to allow direct stimulation of individual photoreceptors.

In one test, subjects were given direct stimulation of a thousand M (mid-range) receptors. That is a novel stimulus. Interestingly, all the subjects reported about the same thing: a deep peacock green. The researchers call this new color olo.

That's a fun story. But more importantly, Oz will be a useful tool for studying vision, including diseases.

* News story: Scientists trick the eye into seeing new color 'olo' -- UC Berkeley scientists created a new platform called "Oz" that directly controls up to 1,000 photoreceptors in the eye at once, providing new insight into the nature of human sight and vision loss. (Kara Manke, UC Berkeley, April 22, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Novel color via stimulation of individual photoreceptors at population scale. (James Fong et al, Science Advances 11:eadu1052, April 18 , 2025.)

There is a section of my page Internet resources: Biology - Miscellaneous on Medicine: color vision and color blindness. It includes links to several Musing posts.

May 2025

Making microlenses using bacteria

May 28, 2025

Microlenses are tiny lenses -- on the order of 1 micrometer (µm) across, about the size of common bacteria.

How do you make lenses from bacteria? Coat them with glass. Even better, according to a recant article, get the bacteria to coat themselves with glass.

The trick to doing that is to use an enzyme that polymerizes soluble silicate ions into a silicate polymer that is essentially glass. The enzyme, called silicatein, is found in sea sponges, which make silicate (glass) skeletons. Insert the gene for making glass into the bacteria. It works. The bacteria make glass (with silicate included in the growth medium), and the glassy bacteria indeed act as tiny lenses.

Silicatein genes from two sea sponges were used in the work: Tethya aurantia and Suberites domuncula. The silicatein gene was fused to the bacterial gene for an outer membrane protein, thus targeting the glass making to the cell surface. The bacteria were Escherichia coli.

And yes, the lenses were alive. The bacteria continued to metabolize for a few months, though they did not divide.

Microlenses are potentially very useful; they should provide high resolution. Making good microlenses has been difficult. This work could open up a new approach for making them easily and inexpensively.

* News stories:

- Can sea sponge biology transform imaging technology? (Lindsey Valich, University of Rochester, December 13, 2024.)

- Living lenses? Glass-coated microbes might take better photos -- Working as tiny, bendable lenses, they could lead to thinner, flexible cameras or sensors. (Katie Cottingham, Science News Explores, April 18, 2025.)

* The article (may be open access): Engineered bacteria that self-assemble bioglass polysilicate coatings display enhanced light focusing. (Lynn M Sidor et al, PNAS 121:e2409335121, December 10, 2024.)

More about sponge glass: Croatian Tethya beam light to their partners (December 16, 2008).

More novel lenses: Graphene bubbles: tiny adjustable lenses? (January 15, 2012).

Iron-helium compounds, which might be reservoirs of helium in the Earth core

May 21, 2025

Subject an object to high pressure, and one might expect it to become smaller. Subject a crystal of iron to high pressure in the presence of helium gas, and the crystal becomes bigger. That's evidence that helium became incorporated into the crystal, with the binding energy more than compensating for the stress of the high pressure.

That's the essence of a new article. And the authors provide some theoretical calculations to support the formation of Fe-He compounds.

What happens when the pressure is reduced -- to ordinary atmospheric pressure? At least some of the new chemicals remain, and can be analyzed by ordinary methods under ambient conditions.

There are many questions, but it is a bit of helium chemistry, and a bit more of high pressure chemistry. And it may offer a solution to the mystery of where the primordial helium-3 is hiding on Earth.

* News story: Centre of the Earth could hold large reservoir of iron-helium compounds. (Tim Wogan, Chemistry World, March 10, 2025.)

* News story from the publisher's news magazine: Iron-Helium Compounds Form Under Pressure -- Experiments show that iron's crystal lattice expands to incorporate helium. (Rachel Berkowitz et al, Physics 18:s22, February 25, 2025.)

* The article: Formation of Iron-Helium Compounds under High Pressure. (Haruki Takezawa et al, Physical Review Letters 134:084101, February 25, 2025.)

More about the possibility of light gases in the Earth core: How much hydrogen is in the Earth's core? (May 22, 2021). From the same labs. The article of this earlier post is reference 31 of the current article.

Also see... Briefly noted... Novel Fe-O compounds in the Earth's inner core? (April 26, 2023).

Red meat allergy (Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS)), ticks, and urbanization

May 14, 2025

This post discusses two distinct but related aspects of the title topic. There are separate articles and news stories for the two issues.

Red meat allergy is a potentially serious immune response to a specific disaccharide of galactose. The offending sugar is often called αGal, and the condition is called Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS).

αGal is ubiquitous. It is present in most mammalian meats -- except primates (including humans). Since we lack it, we are potentially at risk when we consume any (non-primate) mammalian meat. Fortunately, oral ingestion usually does not lead to stimulating the immune system.

However, if an animal injects αGal directly into the bloodstream, that can lead to immune stimulation -- and a serious response upon subsequent oral meat consumption.

Who would inject αGal directly into the bloodstream? Ticks. In fact, AGS has previously been associated with having bites from one kind of tick.

Two new articles extend that work, reporting AGS that seems associated with bites from two more kinds of ticks. A pattern. And maybe we should wonder about the possible role of bites from other insects.

To be explicit, ticks are not transmitting a pathogen here. They are directly injecting a harmful chemical. (It may be that the ticks are transmitting the chemical from one host they have bitten to another.)

A separate article looks for ecological factors that might be behind the increasing frequency of AGS. Increased interaction between ticks and people could be relevant. Urbanization is affecting the habitat of both, and likely increasing their interaction. Climate change is affecting the distribution of ticks; in context, it is generally increasing the range of ticks. One can take the findings as preliminary, but the point deserves attention. The authors suggest that AGS should be a reportable condition at the national level, to allow the development of better data.

Ticks associated with red meat allergy...

* News story: Research ties bites from 2 more types of ticks to red meat allergy. (Mary Van Beusekom, CIDRAP, March 20, 2025.)

* Two articles (both open access):

- Alpha-Gal Syndrome after Ixodes scapularis Tick Bite and Statewide Surveillance, Maine, USA, 2014-2023. (Eleanor F Saunders et al, Emerging Infectious Diseases 31:809, April 2025.)

- Onset of Alpha-Gal Syndrome after Tick Bite, Washington, USA. (William K Butler et al, Emerging Infectious Diseases 31:829, April 2025.)

Ecological factors, such as urbanization...

* News story: Tick-borne meat allergy may be related to urbanization in mid-Atlantic US. (Mary Van Beusekom, CIDRAP, April 25, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Environmental risk and Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS) in the Mid-Atlantic United States. (Brandon D Hollingsworth et al, PLOS Climate 4:e0000528, April 23, 2025.)

A recent post about ticks: How ticks stick (March 26, 2025).

Another food allergy: Carrot allergy (October 25, 2020).

I have listed this post on my page Internet resources: Biology - Miscellaneous under Nutrition; food and drug safety.

Plant-based vs animal-based diets

May 7, 2025

Is one food source better for people?

A new article looks at nearly 60 years of data from over 101 countries, and concludes... It depends. In particular, it depends on how old you are. For young children, an animal-based diet is associated with reduced mortality. For adults, a plant-based diet is associated with longevity.

The analysis is based not on dietary data about individuals, but on the nature of national food sources. It is all statistics, rather overwhelming complex statistics. (Know about the geometric framework for nutrition?) The heart of the article is not easy reading. But it all leads to some general conclusions, with some discussion of what might be behind them.

As always, a single article does not a truth make. But this article offers some ideas that deserve good follow-up. Maybe a nuanced answer to the plant vs animal debate is a step forward.

* News story: This Surprising Protein Shift Could Add Years to Your Life, Study Finds -- A global study ties plant protein to longer adult lives, but early life needs differ. (Tudor Tarita, ZME Science, April 23, 2025.)

* The article (open access): Associations between national plant-based vs animal-based protein supplies and age-specific mortality in human populations. (Caitlin J Andrews et al, Nature Communications 16:3431, April 11, 2025.)

Also see... Briefly noted... Relationship between meat consumption and longevity (July 26, 2022). The work noted in this earlier post reaches a conclusion that seems inconsistent with the current article. The cautions noted in that post apply here.

I have listed this post on my page Internet resources: Biology - Miscellaneous under Nutrition; food and drug safety.

April 2025

Should obesity be redefined?

April 30, 2025

BMI = Body mass index. You can measure it yourself at home. You just need a tape measure and a bathroom scale, and maybe a web page that does the calculation right: your body mass divided by the square of your height, in specified units. Score 30, and you are declared "obese".

Simple, but how useful is it medically? Many people who score in the obese range seem quite fit. As an example of why, the BMI counts muscle mass and fat mass the same.

A new report from an international group of experts examines the situation, and offers some proposals. A simple one is to use additional data to subdivide obesity (BMI 30) into two types: "clinical obesity", and "preclinical obesity". In clinical obesity, there is disease due to the obesity. In pre-clinical obesity, there is not. In this latter case, we can recognize a risk factor, but, perhaps due to other factors, it has not caused disease.

If that still seems simplistic... It is a step. And the full report actually contains more suggestions, with discussion. The report is not just about words, but establishing a diagnostic framework.

There is no new data here, and pretty much no new understanding. It is about communication. We label people, and simple labels may really not serve much purpose. The goal of the report is to develop better communication -- without making it too complex to understand.

News stories. The following items offer increasing levels of detail about the report.

- A better definition of obesity -- New guidelines use more than just body mass index to diagnose obesity. (Kristin Samuelson, Northwestern University, January 14, 2025.)

- Obesity label is medically flawed, says global report. (Philippa Roxby, BBC, January 15, 2025.)

- Diabetes Distilled: Reframing the definition and diagnosis of clinical obesity. (Pam Brown, Diabetes on the Net, March 3, 2025.) The page notes "This website is for healthcare professionals only." This seems to be a copy of an article in the section Diabetes Distilled of a news magazine: Diabetes & Primary Care 27:25, March 2025. For a pdf of the item, use the "Download pdf" link near top of the news story page, or go directly: pdf. Four pages (as pdf). Contains considerable detail, but is still quite readable.

* Editorial from the journal (open access): Redefining obesity: advancing care for better lives. (The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 13:75, February 2025.)

* The article: Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. (Francesco Rubino et al (The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission), The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 13:221, March 2025.) Again, note that this is a report of a commission, not a research article. The article is free, with registration. Or you can get a copy using Google Scholar.

A BMI calculator, with some basic information: Calculate Your Body Mass Index. (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI, part of US NIH).) Also in Spanish.

A post making use of BMI as a measure of obesity: Antibiotics and obesity: Is there a causal connection? (October 15, 2012).

The abbreviation BMI is also used to mean brain-machine interface. Posts on that topic include The brain-machine interface -- at the World Cup (July 2, 2014).

This post is listed on my page Biotechnology in the News (BITN) -- Other topics under Diabetes. (That section does not systematically list posts on obesity.)

The choano-mouse: implications for understanding the origins of transcription factors that control stem cells

April 23, 2025

Differentiated cells from a mammal can be induced into a stem cell state by a procedure involving adding key transcription factors. Those factors for making induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) include the proteins Sox and POU.

Choanoflagellates ("choanos", for short) are single-celled organisms thought to be very near the base of the animal kingdom. Choanos contain proteins recognizable as Sox and POU.

A recent article explores how close the choano Sox and POU are to their mouse counterparts. The most dramatic result is that choano Sox can fully substitute for mouse Sox in making mouse iPSC. Mice, apparently normal, have developed from iPSC made using choano Sox. The conclusion, then, is that at least one protein key to making stem cells existed before there were animals.

As a variation, the scientists calculated the likely sequence of the Sox protein that would have occurred "back then", in choanos prior to the emergence of animals. That predicted ancestral Sox also worked fine.

The situation for POU was more complex. The choano POU did not work in the induction of mouse iPSC.

It is a fascinating study, providing some clues about the origin of animal stem cells. I do suggest caution in interpreting what it all means.

* News stories:

- A Journey back in time to the origin of stem cells -- Proteins that regulate animal stem cells are much older than animals themselves. (Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Marburg, November 15, 2024.)