See top figure for a scale bar. The rotifer is probably a "speck" to the naked eye. The hyphae are probably a few micrometers wide -- easily visible with a light microscope.

The figure is from the Science Daily news story listed below.

This is a supplementary page for the post Lesbian necrophiliacs (March 8, 2010).

Continued ...

Some background

What are rotifers? They are tiny, almost microscopic, animals. Leeuwenhoek saw them, but it wasn't realized they were multicellular animals until the 19th century. They are common, growing in fresh water "everywhere". They are especially common in ephemeral water -- tiny bits of water that last only a short while. They can be found growing in the moisture on mosses.

Why are rotifers interesting? The particular type of rotifer here is the bdelloid rotifer. (And we already have a problem -- one with a simple solution: pronounce bdelloid with a silent b.) What makes bdelloid rotifers particularly interesting to biologists is that they are all female. No one has ever found any evidence for any males or even hermaphrodites in these bdelloid rotifers. They reproduce by cloning; so far as we can tell, they have done so for many millions of years.

So, who cares? Setting aside the jokes... Most types of animals have sex. Sometimes it is obligatory for reproduction, sometimes it is optional, and done only occasionally. But it is done. The lack of sex in rotifers is intriguing; it does not fit with our general view of biology.

Why sex? Ah, that is an important question for biologists. Sex is a rather expensive process -- genetically. A female that reproduces by cloning passes on 100% of her genes; a female that reproduces by sex passes on only 50% of her genes to each offspring. There may be some reason for the predominance of sexual reproduction, but biologists are not sure exactly what it is. Of course, it seems likely that the advantage of sex is that it shuffles genes, thus increasing genetic diversity. But that is a fairly broad idea; can we be more specific? One idea that has been catching on is that the sexual shuffling of genes helps the animal overcome the burden of its microbial enemies or parasites. These simpler organisms typically grow faster and have smaller genomes; one way animals compete in the evolutionary struggle is to shuffle their genes via sex.

Exceptions? In fact, some animals do lose sex, and reproduce only clonally; however they seem to be evolutionary dead ends, and die out fairly soon. The bdelloid rotifers are a spectacular exception: they seem to thrive quite nicely without sex. So, in addition to being a curiosity, they may offer some clue about the role of sex. That is, does understanding an exception help us understand the rule?

And? Turns out that the rotifer story offers some evidence to support the idea that sex is to prevent microbial attackers. Rotifers have an alternative way to deal with their attackers, thus obviating the need for sex.

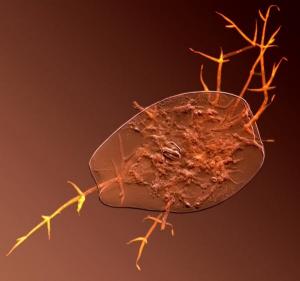

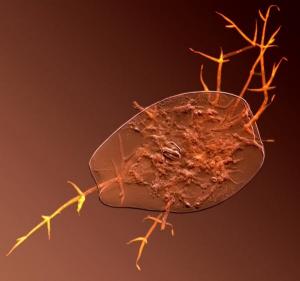

More rotifer trivia. Before discussing the new work, we need to know a couple more things about these rotifers. First they have another remarkable property: they survive extreme desiccation (drying). They often grow in ephemeral water; when the water evaporates, the rotifer dries out -- but survives. Second, their major enemies are fungi; an example of the problem is shown below.

|

A rotifer -- now dead -- with fungal hyphae (filaments) emerging.

See top figure for a scale bar. The rotifer is probably a "speck" to the naked eye. The hyphae are probably a few micrometers wide -- easily visible with a light microscope. The figure is from the Science Daily news story listed below.

|

|

Paper 1 (2010)

So what did they do? Well, they showed that rotifers survive drying better than the fungi that infect them. Further, the rotifers -- very tiny -- are easily blown away by wind. Thus when their water dries up, the rotifers survive and even move to a new home; the fungi that infect them largely die. Cute. If it is right, it lends support to the idea that an important role of sex for most animals is escaping predators -- genetically. Rotifers lack the sex, but have this alternative strategy for escaping predators: they just out-survive their predators upon drying, a normal part of their existence.

Paper 2 (2008)

This paper showed that rotifers have another unusual property: They seem to have horizontal gene transfer (HGT). What's HGT? Well, the usual way to get genes is from your parents; that's called vertical transmission. But we have known for some time that bacteria are pretty good at getting genes from the neighbors -- or more or less anyone who happens to be around. That is called horizontal gene transfer. In bacteria, we understand generally how HGT occurs, through processes such as bacterial transformation or plasmid transfer. However, HGT seems rare in complex organisms.

Here they find that rotifers have HGT: they have an unusually high amount of DNA that obviously came from quite unrelated organisms. Why? Well, remember that drying up we talked about above? During that process, their cells are damaged; even their DNA is highly damaged. One reason these rotifers survive drying is that they have an unusual ability to repair badly damaged DNA. It's quite likely that they pick up odds and ends of DNA that happen to be around, and while repairing their DNA, manage to incorporate some of the "miscellaneous" DNA into their own chromosomes.

But think about it... If they pick up DNA from "anyone who happens to be around", that might include other members of their own population. That is, a dried up rotifer might pick up DNA that had been released by dead rotifers. If that happens, we then have some gene exchange within the rotifer population -- perhaps not very different from bacterial transformation. So, maybe rotifers don't have sex, but maybe they do have an alternative mode of gene exchange. There is no real evidence for this at this point, but it is a good idea worth exploring.

If you are following all this, you now have enough information to understand the title of this post.

And the take home lesson is ...

There is a lot here. What are you supposed to believe? Well, there are some experimental facts, and then there are some interpretations of them. The experimental facts include... Rotifers survive drying better than their fungal predators; dried rotifers are easily blown away to a new home; rotifers contain a lot of foreign DNA. These are experimental results. Unless someone shows that the facts reported simply are not correct (and that happens sometimes), these points are likely to hold. Then we have some interpretations. First, we conclude that drying up and blowing away is how rotifers escape their fungal predators. Or, better, that it is one way. This interpretation is rather close to the actual results; perhaps then it is likely to hold up. And we have some interpretations in terms of big issues: this novel escape strategy seems to act as an alternative to sex, thus suggesting what the natural role of sex is. That point seems logical, but it is also a stretch. Maybe there are multiple roles for sex. Maybe rotifers have other reasons for not needing sex -- with the HGT being one of them. So this broader idea will stimulate discussion and further work; for now, it is an intriguing idea.

Readings, for more information

I encourage you to at least look over the first two news stories listed here. And try the music at the end.

A good news story about Paper 1: Like Escape Artists, Rotifers Elude Enemies by Drying Up and -- Poof! -- They Are Gone With the Wind. (Science Daily, February 8, 2010.)

From the ASM blog, on Paper 2, but also generally about the rotifers and HGT: The Scandalous Bdelloid Rotifers. (M Youle, April 20, 2009.) Now archived.

A blog story about Paper 2: Hot Necrophiliac Lesbian Bdelloids. (December 15, 2008.) Not a particularly good item, but it was the inspiration for the title sent to me.

Paper 1: Anciently Asexual Bdelloid Rotifers Escape Lethal Fungal Parasites by Drying Up and Blowing Away. (C G Wilson & P W Sherman, Science 327:574, January 29,2010.)

Paper 2: Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers. (E A Gladyshev et al, Science 320:1210, May 30, 2008.) This paper is from Matt Meselson's group; that is the Meselson of the famous Meselson & Stahl experiment, back in 1958, showing that DNA replication is semi-conservative.

As I read about the new work, I could not help but think about the answer having been provided many years earlier, even though the context was different. Why haven't rotifers had sex in 30 million years? The answer, my friend, is... Rotifer music.

Return to this topic on main page.

E-mail announcement of the new posts each week -- information and sign-up: e-mail announcements.

Contact information Site home page

Last update: December 9, 2025